Clean Architecture in Django

I have posted this at 21 Buttons engineering blog, the place where I’ve been working last year with an amazing experience :). I mirror here that post, I hope you will like it! Feedback is more than welcome.

Update: I’m working on a little project using this architecture and I’ve published the code on Github: abidria-api

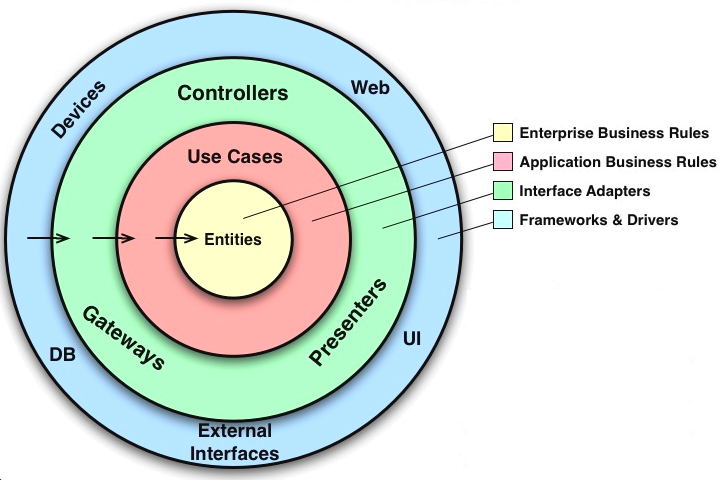

This post will try to explain our approach to apply Clean Architecture on a Django Restful API. It is useful to be familiarized with Django framework as well as with Uncle Bob’s Clean Architecture before keep reading.

To do that, we’ll use a minimalist example of an app with a unique GET endpoint to retrieve a product. Architecture explanation is structured by the same layers as the diagram above. We are going to start with the innermost one:

Entities Layer (Innermost Domain)

Here we define entities.py:

class Product(object):

def __init__(self, reference, brand_id):

self._reference = reference

self._brand_id = brand_id

@property

def reference(self):

return self._reference

@property

def brand_id(self):

return self._brand_idThis is a simplistic example of an entity. A real entity should be richer. Allocate here business logic and high-level rules that are related to this entity (eg: invariant validations).

Use Cases Layer (Outermost Domain)

We call them interactors.py

and they contain the business logic of each use case.

Place here all the application logic.

We use command pattern for their implementation

because it helps with task enqueueing,

rollback when an error occurs

and also separates dependencies and parameters

(really useful for readability,

testing and dependency injection):

class GetProductInteractor(object):

def __init__(self, product_repo):

self.product_repo = product_repo

def set_params(self, reference):

self.reference = reference

return self

def execute(self):

return self.product_repo.get_product(reference=self.reference)Again, this example is too simple. In a user registration, for example, we should validate user attributes, check if username is available against the repo, create new user entity, store it and call mailer service to ask for a confirmation.

Interface Adapters Layer

Here we have pieces that are decoupled from framework, but are conscious of the environment (API Restful, database storage, caching…).

First of all we have views.py.

They follow Django’s view structure

but are completely decoupled from it

(we’ll see how on the next section):

from .factories import GetProductInteractorFactory

from .serializers import ProductSerializer

class ProductView(object):

def __init__(self, get_product_interactor):

self.get_product_interactor = get_product_interactor

def get(self, reference):

try:

self.get_product_interactor.set_params(reference=reference)

product = self.get_product_interactor.execute()

except EntityDoesNotExist:

body = {'error': 'Product does not exist!'}

status = 404

else:

body = ProductSerializer.serialize(product)

status = 200

return body, statusAnd here the serializers.py

(just to show that view returns a python dict as body):

class ProductSerializer(object):

@staticmethod

def serialize(product):

return {

'reference': product.reference

'brand_id': product.brand_id

}ProductView just gets an interactor from a factory

(we’ll see later what that Factory is…),

parses the input params

(could also make some syntactic/format validations)

and formats the output with serializers

(also handling and formatting exceptions).

On the other side of this layer

we have our frontal repositories.py.

They don’t access to storage directly

(these parts are explained on the next layer)

but are in charge of selecting the source storage,

caching, indexing, etc:

class ProductRepo(object):

def __init__(self, db_repo, cache_repo):

self.db_repo = db_repo

self.cache_repo = cache_repo

def get_product(self, reference):

product = self.cache_repo.get_product(reference)

if product is None:

product = self.db_repo.get_product(reference)

self.cache_repo.save_product(product)

return productFramework & Drivers Layer

Composed by Django and third party libraries, this layer is also where we place our code related to that parts to abstract their implementations (glue code).

In our example we have two parts of that kind: database and web.

For the first part we have created a repository that it’s completely tied to Django ORM:

from common.exceptions import EntityDoesNotExist

from .models import ORMProduct

from .entities import Product

class ProductDatabaseRepo(object):

def get_product(self, reference):

try:

orm_product = ORMProduct.objects.get(reference=reference)

except ORMProduct.DoesNotExist:

raise EntityDoesNotExist()

return self._decode_orm_product(orm_product)

def _decode_orm_product(self, orm_product):

return Product(reference=orm_product.reference,

brand_id=orm_product.brand_id)As you can see, both object and exception that this class returns are defined by us, thus we hide all the orm details.

And for the second one we have created a view wrapper to hide format details and decouple our views from the framework:

import json

from django.http import HttpResponse

from django.views import View

class ViewWrapper(View):

view_factory = None

def get(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

body, status = self.view_factory.create().get(**kwargs)

return HttpResponse(json.dumps(body), status=status,

content_type='application/json')The goals of this wrapper are two: convert all the arguments of the request to pure python objects and format the output response (so the views can also return pure python objects).

Also, self.view_factory.create() creates the view

with all its dependencies (we explain it in detail below).

In these layer we also have models.py, admin.py, urls.py,

settings.py, migrations and other Django related code

(we will not detail it here because it has no peculiarities).

These layer is totally coupled to Django (or other libraries). Although, it is really powerful and essential for our app we must try to keep it as lean as we can!

Dependency Injection

But… how do we join all these pieces? Dependency injection to the rescue!

As we have seen before, we create the view with factories.py,

who are in charge of solving dependencies:

from .repositories import ProductDatabaseRepo, ProductCacheRepo

from .unit_repositories import ProductRepo

from .interactors import GetProductInteractor

class ProductDatabaseRepoFactory(object):

@staticmethod

def get():

return ProductDatabaseRepo()

class ProductCacheRepoFactory(object):

@staticmethod

def get():

return ProductCacheRepo()

class ProductRepoFactory(object):

@staticmethod

def get():

db_repo = ProductDatabaseRepoFactory.get()

cache_repo = ProductCacheRepoFactory.get()

return ProductRepo(db_repo, cache_repo)

class GetProductInteractorFactory(object):

@staticmethod

def get():

product_repo = ProductRepoFactory.get()

return GetProductInteractor(product_repo)

class ProductViewFactory(object):

@staticmethod

def create():

get_product_interactor = GetProductInteractorFactory.get()

return ProductView(get_product_interactor)Factories are in charge of creating and solving dependencies recursively, giving the responsability of each element to its own factory resolver.

And finally, the place where all begins: urls.py

url(r'^products/(?P<reference>\w+)$',

ViewWrapper.as_view(view_factory=ProductViewFactory))This post not aims to destroy Django architecture and components, nor misuse it. It’s just an alternative that can be really useful in some kind of contexts.